From the very beginning of our National History Bee preparation process I planned on using flash cards to help Everest remember what she was learning. We were living in Montenegro at the time so there was no easy way to buy them on Amazon. Instead I went to a local store and bought some cardboard, scissors, pens and ziplock-like bags. I cut up the cardboard, wrote on the back and front and threw the cards into the biggest bag.

My original plan was to use the “Leitner System”. The system is simple. You start by using the new cards normally. If you get a card right you move it to Box 2. If you get it wrong is stays in Box 1. You review Box 1 frequently (every day, but you could do it more if you like). Box 2 you review every few days. If you get a card in Box 2 correct you move it to Box 3. If you get it incorrect, you move it back to Box 1. You review Box 3 less frequently (say once a week). Any time you get a card correct you move it to a higher number box that is reviewed less frequently. When you get it wrong it drops all the way back to Box 1.

The idea is that the stuff you forget you review a lot. But once you have something in your long term memory you need to review it less frequently (but still sometimes). The better you know it, the less frequently you need to review. It is a great system — if you don’t have a better one.

The problem with Leitner is that it treats all cards the same. It means that there are some cards you are reviewing too much (wasting time) and other cards you are not reviewing enough (so they won’t stick in long term memory). But if you just have paper and cardboard and ziplock backs it is a much better than reviewing every card every day.

But technology has come a long way since 1972 (when Sebastian Leitner proposed the system).

I’d like to say I did my research and never wasted any time with Leitner. That would not be true.

I spent way too many hours cutting cardboard and writing flashcards.

Then I spent more hours moving from cardboard to an app-based version of Leitner cards.

Only then did I re-discover the Anki system.

Anki is a free open-sourced product (the organization does not charge for the desktop app or web-based version. There is an unaffiliated group that offers a free Android app. The main organization charges $25 one-time for the iOS app as their only source of income). Instead of cards moving between virtual boxes, Anki can, based on your prior performance in getting cards correct, calculate a forgetting curve for every card in your deck — and then push the card back into your daily task just before you forget it.

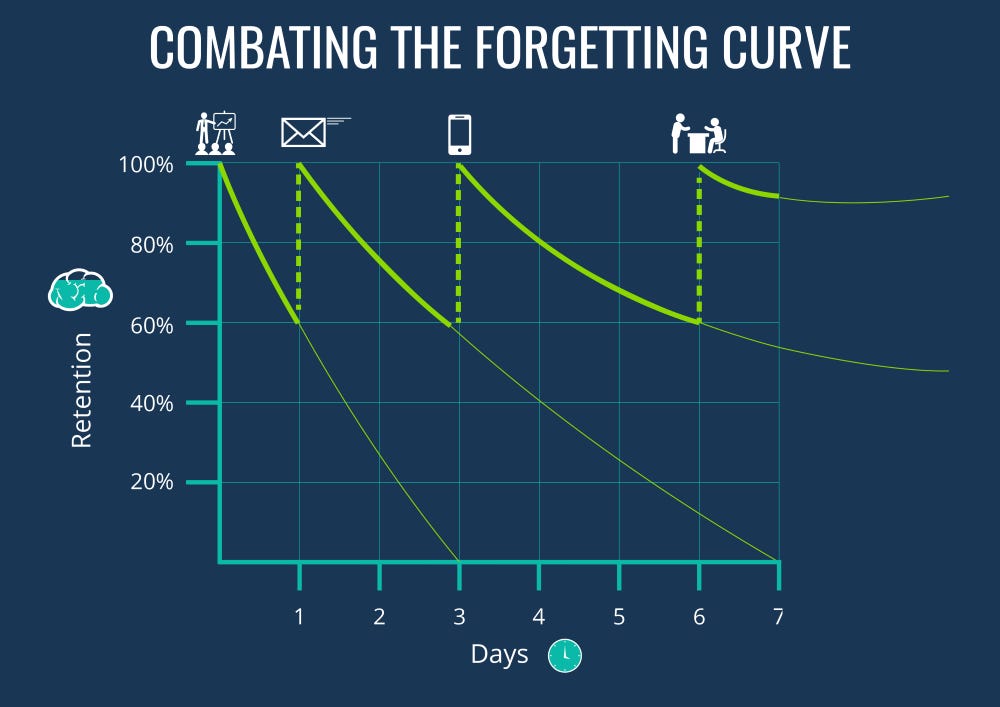

Here is what a forgetting curve looks like (with spaced repetition reviews):

(Source)

There is a huge community built around Anki (mostly language learners and med school students). If you want to learn more I highly recommend the guides created by the Anki subreddit. For the rest of you, here is an amateur’s version of what I have learned about setting it up for success. These are three main settings to play with:

Number of new cards per day: You create a queue of cards you want to study. The system limits how many new cards it pushes to you in a given day. The recommendation is 20, and that is a pretty good place to start. But when you are FIRST starting getting through 20 cards is not very difficult nor time consuming. I had Everest on 45 cards for a while, but that is just a sprint when we had the time on a long road trip. She has recently missed a few days (See more on that below), so we have dropped down to 10 cards/day until she gets caught up with her backlog. I have just started using Anki myself and I am doing 90 initially — but that is just to kick things off, and I will lower it very soon (see why below)

FSRS: “Free Spaced Repetition System” — this is a switch you will want to toggle as soon as you start with Anki. It is just a better algorithm for which cards Anki will send back to you (it has only been available for about 12 months, so they have not made it the default yet. As far as I am aware there is no good reason not be using it!)

Recall Rate: Once you have selected FSRS you need to decide what successful recall rate you want to have.

Recall Rate deserves its own mini-deep dive:

The default recall rate is 90% — which means that 90% of the non-new cards Anki shows you each day you should be able to get right. You can move that number up or down, but generally you will not want to.

If you set that number lower than 90% then you can wait longer before each card is shown again. This reduces your workload. But only in theory. In practice lower retention means that you will struggle more to answer each card. This has tow bad side effects:

It’s less fun. Struggling and getting things wrong is a lot of work. Learning is hard enough. You just made it harder

It takes longer. If you don’t know the answer quickly, you will take longer to complete each card. So even though you are reviewing each card less frequently, if it takes 50% longer to get through a card, you may end up spending the same amount (or more) time, and just have lower retention

If 90% is so good, why not set it higher?

You could, but then you run into a different problem. Remembering correctly 95% of the time is not 5% harder than remembering 90% of the time. You need to reverse it — its the difference between forgetting 5% of the time vs 10% of the time — and that is a 2x difference. So moving recall rate above 90% results in an exponential increase in the number frequency cards will be pushed back to you. The chart looks like this:

(Source)

Notice how workload for 50% retention is actually higher than 80% retention. 80% is a little less work than 90% but not by much, but 95% is twice as much work as 80% and 96% is triple.

It may make sense to lower retention to 80% or increase it up to about 95%, but you really don’t want to leave that range.

How does Anki work in Practice?

At the start and at the end of each session you will want to “synchronize”. Synchronizing pushed all the local metadata on your device to the cloud, and pulls any data from the cloud onto your device. This SHOULD happen automatically, but it doesn’t. If you forget to do this you could end up with your different Anki devices being out of sync, with no way to get them back into sync without eliminating the information on one of the devices. You have been warned. (I made this mistake once and only once).

Each deck queue has cards in three categories:

New: These are the new cards that you have not been exposed to yet that are in the queue to be answered that day (at whatever limit you have set)

Due: These are cards that you have answered correctly in the past that Anki’s FSRS algorithm thinks you need to review today. You can also set a cap on this number if you like (but you should not)

Learn: These are cards that you answered incorrectly, that Anki wants you to review again. If you “finished” all your cards from the day before you should start with nothing in this bucket. But as soon as you start answering cards they will move here when you get one wrong.

The rest of the cards sit in the library to be pushed out on a different day.

When you start a session it will push you a card. You answer it (ideally out loud), and then press a “reveal” to reveal the answer. Then you have four choices:

“Again”: You did not get it right. Even if you got it “close” you should be pressing this button

“Hard”: You got the right answer, but you struggled to get there

“Good”: You got the right answer, but maybe fumbled a little or did not do it fast

“Easy”: Like it sounds.

Based on your history with the individual card, and your history with cards in general, and the button you pressed, the algorithm will tell you when it will push back the card in question. If you pressed “again” this will often be a few minutes later (sometimes as much as ten minutes. Sometimes less than one minute — i.e., it will give you another card, and then come right back to this one). Even if you press “Hard” or “Good” it will sometimes bring the card back again in the same session (at least a few times. If you hit good enough times in the same day, it will eventually push it to the next day).

How Long Does This Take?

The Anki community’s “rule of thumb” is that when you are at scale one new card per day takes ~one minute. That does not mean answering a card takes a minute. It means that if you have been consistently adding ~20 cards/day over an extended period of time, then the total of new cards plus due cards plus learn cards should take ~20 minutes (all assuming you have things set at a ~90% retention rate).

Anki itself recommends that the “maximum cards per day” be set to at least 10x the max new cards/day. Which means that on average it will take ~10 exposures to a card before it has been so solidified into your long term memory that you will not need to review it again for years.

This also means that you CAN increase the number of new cards per day on an ad hoc basis without killing yourself. If you normally have been doing 20 cards/day for years and it takes you 20 minutes, then one day of 100 cards might take you an extra 10 minutes. Then tomorrow you may need to spend an extra 5 minutes as you have extra review on those new cards. Then the day after your review may take 24 minutes, then 23, then a week at around 21-22 minutes, before dropping back roughly to 20 minutes again. (I have not checked any of that math, but hopefully you get the idea).

It also means that you can front load things. When you are first starting out reviewing 20 new cards (and no old cards) should only take ~5 minutes. Maybe you can do 40 or even 100 cards for a few days to kick things off, then lower your daily total down to 50, then 30, and so on as the review numbers increase. That is what I am doing with my own deck right now. I have decided I want to better understand what Everest is going through so I am picking historical stuff that I do not know well and building my own Anki decks to review. I started with 90 new cards per day learning about Chinese Dynasties and Roman Emperors. I will ramp down the number of new cards over time.

What Does This All Mean?

My big takeaway is that every day matters.

If you are willing to commit 20 minutes/day to imprinting things into your long term memory, then you get to have 20 new things per day added to your memory. That’s it. And if you miss a day, then those 20 things you could have added as just “gone”. The only way to get them back is to try and do 40 on the next day — but if you to that it will, on net, take you significantly more than 20 minutes - the day you learn 40 things is a LOT harder than learning 20 things, and then you need the time for those things to be reviewed over the next weeks and months — and because they were attempted on “40 per day” instead of “20 per day” your recall is likely to be lower, which means more frequent reviews.

ALSO: If you miss a day then all the review you needed to do gets pushed to the next day. Not only will your review take twice as long tomorrow, but your success rate on that review will be lower (since you have had an extra day to forget), which means the review part of your session tomorrow will be MORE than 2x as long. You have not really gained anything by missing a day — you will need to make up those 20 minutes in the future AND you will have forever lost those 20 things you could have added to your long term memory.

Anki is a super power

For a given time commitment, it will maximize the number of things you can put into your long term memory. But that doesn’t change the fact that in order to add more things, you need to put in the time and effort to do it.

My bet is, is that in something like the Spelling Bee there are kids and parents that have optimized both time and effort. Kids are spending hours per day preparing and studying using the latest tools.

My more relevant bet is that is NOT happening with the History Bee — at least not yet. And that there are very few if any other kids (especially 4th graders) who are spending 20 minutes per day with an Anki-system learning history. That means that even if Everest is behind a bunch of Tiger-mom-driven kids today, she might be able to overtake them by next May (for Nationals) just by studying smarter rather than harder - 20 new facts per day for six months is 3,600 facts. That’s not everything, but its a lot! And with Anki, those facts are ingrained deeply into long term memory.

What’s Next?

In the process of writing this post I managed to get sidetracked a half dozen times. Topics I will come back to in future posts:

Why aren’t more people using Anki? Why isn’t it in the school system?

How to achieve better learning performance (learnings from “Peak”)

My experiences with niche competitive activities (like lifeguarding)

Motivation: How to get kids using Anki cards as a daily habit

Younger kids: My experience using Anki with my 7-year old

The value of memorization (vs understanding things)

Thursday’s post will be about preparing for Nationals, and then this weekend Everest has her first Regionals. Next week I expect to debrief how that went and how the experience will make me change all my future carefully laid plans. Stay tuned.

Everest’s Instagram

Here is Everest explaining the Korean War:

Keep Learning,

Edward (and Everest)

Hi Edward: would be very interested in a post that discusses how to make effective / ineffective Anki cards for historical topics (how long to make them, how many items to test per card, etc.)